When it first became clear that the COVID-19 pandemic would have catastrophic consequences on our economy, many analysts looking for answers turned to our last economic crisis: the Great Recession of 2008. But a consensus quickly emerged that the COVID-19 shock of 2020 was different in significant ways.

To better understand how to respond to this crisis, we also need to understand what makes it unique. So we reached out to more than a dozen experts with the same question: “What is the biggest difference between the 2008 and 2020 economic crises and why is that important?” Their answers touch on different challenges facing us, from macroeconomic policy, to the particular challenges faced by women and personal support workers, to the changes being ushered in by a rapidly digitizing society.

If you would like to share your thoughts on this question, you can join our Video Town Hall on Thursday, or email us with your own answer.

Paul Boothe: A supply-side recession requires a different playbook than the one we used in 2008

Mike Moffatt: 2020 is a supply shock and a demand shock

Tony Bonen: The speed and magnitude of job losses in 2020 are entirely without precedent

Paulette Senior: The 2020 crisis is having an unprecedented gendered impact in Canada

Danielle Goldfarb: The kids are at home – and that’s a game-changer

Angella MacEwan: The 2020 crisis has put a spotlight on the importance of the care economy

Jenny Ahn: We now have no excuse to ignore the vulnerability of personal support workers

Mohammed Hashim: The pandemic has revealed our reliance on gig workers and our need to protect them

Anna Triandafyllidou: Solidarity movements are rising up to support the most vulnerable

Brian Kelcey: For cities, this downturn isn’t just deep – it’s broad

Steve Orsini: The COVID-19 pandemic has sped up the digitization of society

This supply-side shock is devaluing capital assets and productivity in ways that cannot be addressed using traditional tools

Ken Boessenkool – Founding Partner, KTG Public Affairs

The 2008-09 recession was a demand-side recession. A financial crisis caused companies and individuals to spend less and caused economic activity to slow. The playbook for this kind of demand-side recession is to pump more money into the economy through monetary policy – lower interest rates – or replace some of that lost private demand with public demand through government spending.

In contrast, the current COVID-19 recession is primarily a supply-side shock recession. And no amount of monetary or broad-based fiscal stimulus will open up middle seats on planes, eliminate childcare constraints on primary caregivers, or undo the loss of productivity from physical distancing in our factories.

Ongoing physical distancing rules will devalue capital – a supply-side shock – across the economy, particularly in the service sector. If we ban middle seats on airplanes, the value of a plane will immediately drop. If we limit the number of people in our stadiums, childcare centres, hotels and barbershops, the value of those businesses will drop. No amount of monetary or fiscal stimulus will fix this destruction of capital.

Physical distancing and disinfecting rules will also cause a drop in productivity in the goods-producing side of the economy. Meat-packing plants will never operate at anywhere near their former levels of efficiency. No amount of monetary or fiscal stimulus will restore this lost productivity.

The challenge to the COVID-19 economic recovery will be addressing a supply-side shock that will hit industries where workers or customers have traditionally operated in close quarters, as well as primary caregivers – mostly women – in dual-income families with children.

And these challenges will not be solved using monetary or fiscal stimulus.

A supply-side recession requires a different playbook than the one we used in 2008

Paul Boothe – Faculty Director, Ivey Academy’s Senior Public Sector Leaders Program, Western University

There is a big pothole in the road up ahead and we need to stop looking in the rearview mirror if we want to avoid it. I’m talking about assuming that traditional anti-recession policies will work in the current downturn.

Your usual recession is caused by a demand shock – for example in 2008, bad financial market regulation froze markets and caused a U.S. housing price crash. This put a ton of mortgages underwater, and destroyed the personal wealth of millions of American consumers. It took years for them to rebuild their finances.

Governments and central banks around the world responded in traditional ways. They drove down interest rates, flooded the economy with liquidity, and started spending like crazy. It wasn’t perfect, but it worked. Within a few years, the global economy was chugging along again, albeit from a permanently lower starting point.

This time, however, we are facing a supply shock – something we haven’t seen the likes of for almost 50 years, since the oil price jump in the 1970s. The pandemic has essentially made a whole lot of our capital equipment less productive – and the workers who use it, too.

Low interest rates and government infrastructure spending won’t fix this. We need a new set of targeted policies to help us transition to the post-pandemic reality. Owners of some capital will have to make major changes in how they operate. Others will take big losses and perhaps fail. Taxpayers can’t afford to shelter them all from the new reality.

Hopefully we won’t waste a lot of time and money on the old policies. We still have time to recognize the pothole we’re speeding toward. Now is the time to think about a new set of policy tools to help us transition to a fiscally sustainable, post-pandemic world.

The best way to address supply-side shock adjustments is to support public health measures

Kevin Milligan – Professor of Economics, Vancouver School of Economics

The main difference between the 2008-09 financial crisis and today’s pandemic-induced recession is which side of the economy was hit: demand or supply.

In today’s pandemic recession, the virus itself and public health regulations have shut down entire markets for goods and services. It is not lack of spending power from the demand side, as we saw in 2008, but consumers’ inability to purchase the same basket of goods and services, either because of fear for workers’ or consumers’ safety or because of public health fiat.

These differences between the financial crisis and the COVID-19 recession have starkly different implications for economic recovery.

In 2009, the path to recovery was to re-stoke demand by promoting investment, injecting cash into households, and ensuring financial-sector balance sheets were able to support a resumption of lending.

Today, family income and business cash support are necessary to keep the economic engine idling. These actions stave off bankruptcies or excessive debt that would weigh down demand going forward. However, we will not get the economy back to full speed with these demand-side measures alone so long as the virus restricts economic activities. Getting to full speed will require large supply-side adjustments in the ways of work (socially distanced workplaces), the ways of households (caregiving and working from home), and the ways of consuming (travel and public events such as concerts or spectator sports).

The costs and challenges of those supply-side adjustments are daunting. The best way to minimize these costs is to strongly support public health measures needed now to suppress the virus sharply.

2020 is a supply shock and a demand shock

Mike Moffatt – Senior Director, Smart Prosperity Institute

While no one would argue that there isn’t a supply shock happening, Canada is also facing a demand shock of roughly similar proportions, if not larger.

What I think the demand-shock naysayers are missing is that supply-side triggers can induce demand shocks. A couple of hypothetical examples, to illustrate my point:

- Suppose a tornado rips through the U.S. Midwest and takes out several auto assemblers. Classic supply shock. But in Canada, this would largely manifest itself as a demand shock, as our auto parts suppliers would have lost all of their customers. Foreign supply shocks can trigger domestic demand shocks.

- Now suppose that the tornado instead hits southwestern Ontario and takes out auto assemblers there. Obvious supply shock in Canada, but there’s a demand component to it as well, as those workers are no longer employed, auto parts suppliers still take a hit, etc.

My argument is that versions of both are happening during this crisis and will continue to persist.

Whether or not there’s a demand-shock worth talking about may seem like an academic point, but it drastically alters the path of the economy over the next few years. In particular, each view of the world generates drastically different paths for economic variables:

- Supply-side only: 1970s-style stagflation. Moderate economic decline. Substantial increases in nominal interest rates. Inflationary pressures that either force the Bank of Canada to abandon the 2 per cent inflation target or to hike interest rates even further.

- Supply- and demand-side shocks: Much larger economic decline. Relatively modest impact on inflation and interest rates (the pressure could be upward or downward, depending on the relative magnitudes of the shocks). No stagflation.

That’s two very different sets of predictions, particularly when it comes to nominal interest rates.

The speed and magnitude of job losses in 2020 are entirely without precedent

Tony Bonen – Director of Research, Data and Analytics, Labour Market Information Council

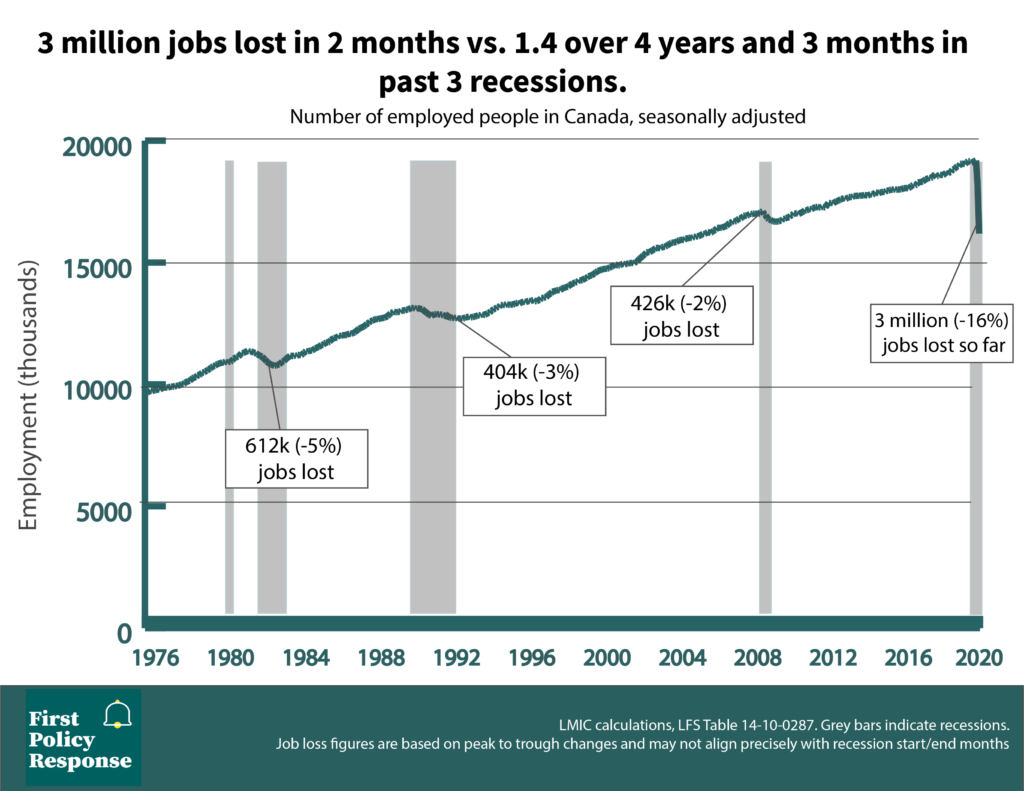

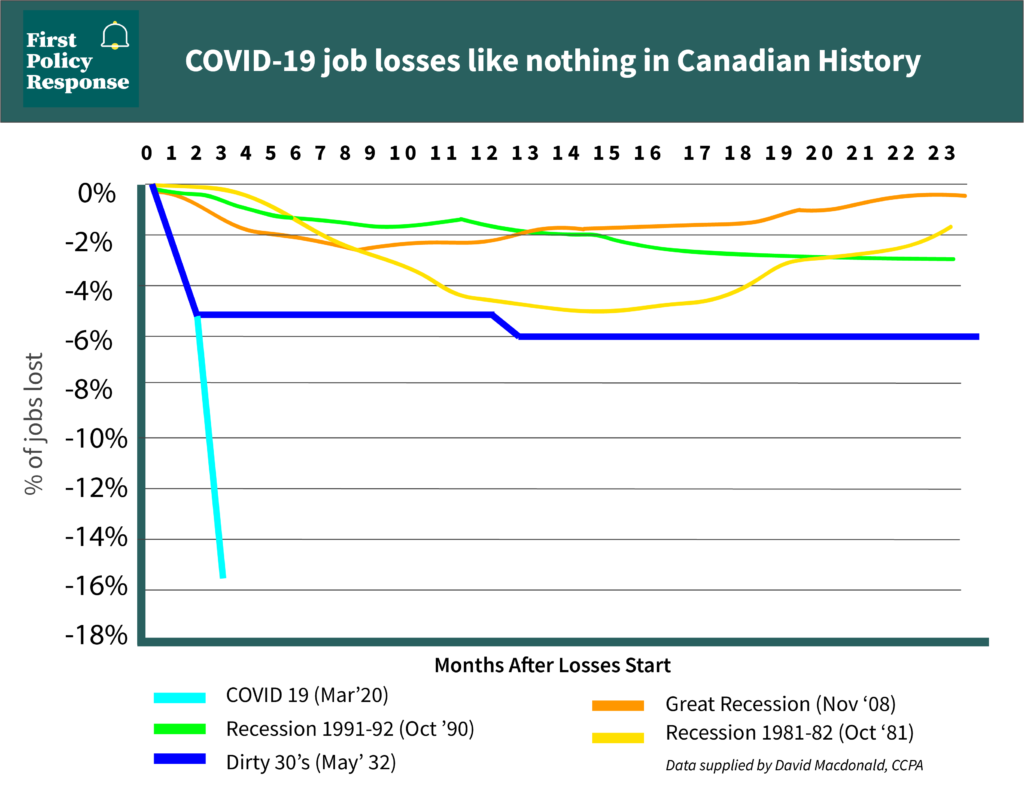

The economic impacts of the COVID-19 crisis are still unfolding, but it is already clear that the speed and magnitude of job losses are entirely without precedent in Canadian history, including any comparison to the 2008 Great Recession.

In just two months, three million jobs were lost across Canada – representing a decline of 16 per cent. As the figure below shows, that’s more than twice the number of jobs lost through the previous three recessions combined, which collectively took more than four years to shed 1.4 million jobs. During the Great Recession, employment fell by 2 per cent from peak to trough (17.1 to 16.7 million) over the course of eight months (October 2008 through June 2009).

In 2020, the unemployment rate also spiked between February and April from 5.7 per cent to 13.0 per cent, well above the 8.7 per cent peak in 2008. Depending on what happens in the coming months, it is possible that job losses will accumulate further and increase unemployment to the estimated 19 per cent unemployment rate seen only in 1933 during the Great Depression.

Given the public health nature of this year’s “Great Cessation” in comparison to Great Recession, many of the job losses are, for now, “temporary layoffs”. This provides some hope that a rapid, V-shaped recovery of employment is possible as the economy re-opens. Thankfully, fiscal policy and monetary authorities reacted quickly to this crisis by rolling out, for example, the Canadian Emergency Relief Benefit, to which 8.25 million Canadians have already applied. Continuing support for those who cannot return to work will be essential for ensuring those who have lost their jobs can make ends meet until we return to a more normal, but different, world. On Friday, when Labour Force Survey data for May is released, we’ll have a clearer view of the dynamics of the rapidly changing economic situation.

Pandemic forced governments to find new ways to get money into Canadians’ pockets, quickly

David Macdonald – Senior Economist, Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives

The job losses during the Great Recession of 2008-09 were a garden party compared to what has happened since March 2020. You have to go back to the Dirty ’30s to see anything like it but, even then, the comparison stops after the first month.

By May 27, 2020, 43 per cent of everyone working in February had received the federal government’s emergency benefit.

The playbook response to this sort of crisis since the 1980s has been to lower interest rates, encouraging businesses and individuals to take out loans and go buy things. The jobless would apply to Employment Insurance (EI).

The pickle this time around is that private debt is already at a record high. Households face record-high mortgage debt while businesses have been gorging on debt to buy out their competitors and boost paybacks to shareholders.

Add ultra-low interest rates into the mix and there was little elbow room: rates were immediately cut to almost 0 per cent in the first month.

What’s unique this time around isn’t just the depth of the crisis, but governments’ massive move to direct cash transfers in the absence of other options.

In the past, EI was the mechanism to help the jobless. This time, EI just crashed. It had to be replaced, on the fly, with the more rapid and expansive Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB).

Government went much further than that. Anyone receiving major federal transfers—the GST credit, the Canada Child Benefit, and seniors’ benefits (OAS, GIS)—also found extra money in their accounts.

This represents a seismic shift in how we fight recessions when private debt is high and interest rates are low: instead of encouraging debt, we put money into people’s pockets at an unprecedented scale.

The 2020 crisis is having an unprecedented gendered impact in Canada

Paulette Senior – CEO and President, Canadian Women’s Foundation

This 2020 economic crisis is having an unprecedented gendered impact in Canada, and it’s shining a light on longstanding inequities.

The 2008 crisis had a high impact on industries dominated by men, such as construction and manufacturing. Today we’re seeing high impacts on service jobs marginalized women often do: servers, cleaners, retail workers and professional caregivers. This “women’s work” tends to be underpaid and it’s precarious at the best of times. In fact, many refer to the current crisis as a she-cession. And with the pandemic, there are even more risks to worry about — not just work interruptions and precarity, but also increased risk of contracting the virus. In Canada, more women than men have been diagnosed with and died from COVID-19, as of June 1.

Statistics show that women in Canada also carry more unpaid caregiving responsibilities than men, including childcare and elder care. With the strain on health services, daycare and school closures, and isolation measures, women have had to take on increased unpaid caregiving needs. For some, this can translate to less time for paid work and having to leave their jobs.

As economist Jim Stanford noted, our current circumstances spotlight how undervalued professions and undervalued workers are crucial to our daily wellbeing. These workers keep us all alive — and they are often women who face multiple forms of marginalization. We don’t need to go back to the way things were. We need a new normal. That’s one of the reasons why we’re calling for a rigorous gender-responsive approach to this crisis.

The kids are at home – and that’s a game-changer

Danielle Goldfarb – Director of Global Research, RIWI Corp.

I’m submitting this note late because I’m struggling — like many around the world — to do the near-impossible: parent while working. There are many differences between the financial crisis and the COVID-19 economic crisis. But one that is neglected in many economic analyses is that this time, the kids are at home. Worse, there is no clear strategy and timing to address this, in turn jeopardizing the economic recovery.

In contrast to the 2008 financial crisis, during COVID-19, governments in Canada and around the world have deliberately shut down the economy and schools, and have paid workers to stay home. But income support will run out soon, at least here in Canada. Parents’ anxiety levels are mounting with concerns not only about paying their bills if they have lost a significant share of their income, but also about leaving their kids at home on their own if they need to work, and then again with each email cancelling yet another summer camp. Google searches for above-ground pools have surged in recent weeks in Canada as parents with the means to do so search for something — anything — for their kids to do all summer. So far, parents and kids have been told little about what they can do, and a lot about what they can’t do: go to school, camp, the park.

This matters because getting the economy back in action requires a clear path to childcare. That path depends on parents trusting that there will be safe and workable solutions — and soon — that allow parents to work either at home or elsewhere if their jobs require it.

Will women, discovering that working and parenting simultaneously is not sustainable over long periods of time, or that they don’t feel safe sending their kids to school, simply drop out of the labour force, making it difficult for them to re-enter for years to come? At RIWI, we ask 1,000 Canadians every week on a continuous basis about their working status, and as of the end of May, more women reported being unemployed but not looking for work compared with the end of April.

There isn’t a clear path to childcare yet, and until we prioritize one, we risk worsening the severity of the crisis and the duration of the recovery.

The 2020 crisis has put a spotlight on the importance of the care economy

Angella MacEwan – Senior Economist, CUPE

If the 2008 economic crisis was about the global economy’s financial infrastructure, the 2020 economic crisis is about our social infrastructure. The 2020 economic crisis has put a spotlight on the importance of the care economy in a way that no other economic crisis or recovery has done. Understanding this will help us chart a successful path out of the crisis, and to build a more resilient economy and society in the future.

Canada’s capacity to respond to the crisis was diminished because we had not properly funded or regulated health care and long-term care. Standards for ICU capacity, staffing ratios and personal protective equipment were insufficient and often not enforced. The unpaid care work of patients’ families that had served to quietly pick up some of the slack from chronic understaffing was suddenly not available.

Families that now had to take on more care work at home had a new appreciation for the importance of a wide cross-section of low-wage care workers – from personal support workers and cleaners to education assistants and early learning and childcare providers. These workers are primarily women, and disproportionately racialized. Weak labour standards and lack of enforcement encourages a reliance on precarious work, and those workers are less able to speak up to ensure their own health and safety, and the health and safety of those they care for.

This recovery will not be the same as other recoveries. The answer is not in more shovel-ready physical infrastructure, but in a reimagined social infrastructure. Care work should not be provided at the mercy of the market, but should be viewed as essential infrastructure for a well-functioning economy and society.

We now have no excuse to ignore the vulnerability of personal support workers

Jenny Ahn – Labour Relations Consultant and Former Assistant to the National President, Unifor

In 2008, the global financial crisis saw 400,000 job losses that affected many people of varying sectors and income levels. With COVID-19, we have hit a historic high unemployment level with more than three million job losses, and we still don’t know the final numbers. We are now seeing the cracks in the service sector being split open due to decades of the spiral downwards in wages, the deterioration or lack of medical benefits, and the deficiency of full-time positions – particularly in the health-care sector serving long-term care homes.

It hurts to see the number of deaths of seniors in long-term care homes. But it also hurts to know that there are mostly unsung heroes who are also dying along with our elderly.

In every country and in every community, front-line health-care workers during this global pandemic have been called heroes. But there is a hierarchy of importance among the various health-care workers. Often near the bottom rung are personal support workers (PSWs), the people who are taking care of our loved ones in long-term care facilities.

These workers did not receive the same level of thoughtfulness and regard for their health as others in the heath-care field. They are often working without being provided with proper personal protective equipment and without adequate training. Is this the unspoken truth of how we undervalue the lives of people once they become elderly or frail? Is this the unspoken truth of how we undervalue particular workers in the health-care field?

So why is there this disparity between health-care workers? Dare I say it out loud? PSWs are overwhelmingly represented by women and workers of colour. They are low- or minimum-wage earners often working two or three part-time jobs to cobble together enough hours to make a full-time job.

We call them heroes today but make their lives precarious and pay them poverty wages.

Let’s ask each other the uncomfortable question: If COVID-19 did not happen, would we even confront this situation, seeing as the alarm bells have been ringing for decades? If we are truly in this together as we prepare for a sustainable recovery, this sector must be addressed in a meaningful way that is not focused on for-profit care. We can start by creating more stable full-time jobs, by compensating PSWs in a way that shows our respect and appreciation for the care they provide to our loved ones, and by providing more time to provide better care for the residents in long term homes.

Leave no one behind and let’s truly be in this together.

The pandemic has revealed our reliance on gig workers and our need to protect them

Mohammed Hashim – Senior Organizer, Toronto and York Region Labour Council

During this pandemic many of us have relied on the service of gig workers – including those who deliver groceries, restaurant meals and even medicine. Our governments have deemed them essential to the functioning of the economy, yet failed to protect them adequately.

In Canada, close to 10 per cent of all workers are employed within the gig economy. Most tech companies portray these jobs as “side hustles,” and for some that is certainly the case. However, the vast majority of workers in the gig economy are doing it full-time, or even more. The more you work, the more you get paid (sometimes), and if you can’t make a decent hourly wage, you end up working more.

The work can also be dangerous. Take the example of bike couriers for Foodora, the food delivery giant. The job appears simple – you pick up food and you drop it off – but most bike couriers work with the mentality that is only a matter of time before they get injured at work.

That was the primary incentive for these workers to form a union – to ensure they could collectively bargain for health and safety provisions, as well as salaries and benefits. On Feb. 25, the Ontario Labour Relations Board ruled that Foodora couriers should be deemed dependent contractors, and therefore would be eligible to receive collective bargaining rights as employees. In response, Foodora closed its Canadian operations on April 27.

The gig economy is likely to play a pivotal role in the future of work, and the government needs to ensure employers are playing by the rules. As we re-open the economy, many employers will likely have less physical office space, and perhaps have a weaker sense of connection to their employees. That could lead to a proliferation of “independent contractors” as opposed to employees. Policy-makers have a choice: either let businesses use the rules to take advantage of employees, or close the door tightly on how we define independent vs. dependent contractors, to ensure we protect the workers of today and tomorrow.

Solidarity movements are rising up to support the most vulnerable

Anna Triandafyllidou – Canada Excellence Research Chair in Migration and Integration, Ryerson University

Both the 2008 and 2020 crises started locally (in the U.S. in 2008, in China in 2020) but they quickly escalated to a global level through a sort of chain reaction. The difference is that in 2008, countries had little power to shield themselves off, while in 2020, those who reacted early have been better able to address the pandemic. In a health crisis, prevention matters.

In either case, the most vulnerable are paying the price – those with less money, less secure jobs and living in poor housing. This includes migrants and asylum-seekers in particular, people with precarious legal status. But we seem to have learned a thing or two since 2008: government action has been faster and more efficient compared to 2008, to assist and support workers losing their jobs, families in distress and people with fragile health.

Another lesson learned: The 2008 crisis gave rise to important transnational protest and solidarity social movements, such as the Indignados in Spain and Greece, Occupy Wall Street in the U.S., and the protest rallies across Europe and the world that played a role in changing the political landscape, at least in Europe. While most movements had died out by the end of the 2010s, this belief in the power of citizens to self-organize and drive change has remained. Local and transnational solidarity has been one positive aspect of this new, dramatic global crisis, as volunteers have hurried to support the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK, mutual aid networks have proliferated globally, people have found public ways to express support to each other even when confined to their homes, and governments have united in their pledge to support crucial research for a COVID-19 cure and vaccine. This is certainly different compared to 2008.

For cities, this downturn isn’t just deep – it’s broad

Brian Kelcey – Urban public policy consultant

For city budgets, what makes the 2020 crisis distinct from the Great Recession is the unusual breadth of it, which is directly related to the unusual cause of it.

In 2008-09, the U.S. housing bubble collapsed, crushing mortgage markets, crushing financial institutions and crushing the broader economy, which in turn led to even more residential mortgage defaults. American cities saw sales tax and real estate excise taxes drop, while taking big hits to investment income, which fuelled big pension shortfalls (and eventually, Detroit’s bankruptcy). But residential property tax revenues stabilized after steep rate hikes on the surviving tax base and vulture-fund buyouts of empty houses. Canadian housing markets didn’t crash, so our “Great Recession” felt more like a typical recession for city budgets.

But 2020’s pandemic is crushing everyday commerce, spreading damage up and out from the bottom of the economy. After businesses laid off rent-paying service employees and defaulted on commercial rent payments, creating downstream risks for property tax collections on millions of units. Many cities deferred property tax collections, creating a cash flow crisis alongside medium-term deficit risks (which is why Ottawa just forwarded infrastructure gas tax transfers to Canadian cities months in advance). Lockdowns and transit safety protocols took out more than 80 per cent of fare revenues. Cities and local agencies (like Metro Vancouver’s Translink) that get direct gas tax revenues for operations costs saw those vaporize. Revenues from parking, fees and even fines and penalties disappeared.

Predictions are tough given the sheer number of uncertainties. Take just two possibilities: if commercial property tax collections slow down, city budgets will be hobbled, because Canadian cities tax businesses at rates 1.5 to 3 times higher than single-family properties. And shifting property values for office towers and storefronts may also cause havoc with tax assessments. For cities, the revenue collapse from the shutdown may just be the first in a series of major financial hits to manage.

2020 crisis has hit frontline tourism and hospitality workers far more disproportionately than in 2008

Adam Morrison – President and CEO, Ontario Tourism Education Corporation

The impact of COVID-19 on the tourism and hospitality sector has been rapid and devastating – with massive closures, layoffs and a tough road to recovery ahead. Statistics Canada data from early May 2020 shows that hospitality and tourism employment has decreased by 43.3 per cent since related shutdowns began, and the overall unemployment rate for the sector is now at 28.8 per cent.

The COVID-19 pandemic has driven the global economy head-first into uncharted territory seemingly overnight. Although initial comparisons to the 2008 financial crisis are instinctive, this is an entirely new animal. This crisis is uniquely tied to human health and wellbeing. The resulting economic disruption is largely workplace-based in that workers, customers and guests simply cannot interact. It’s forcing us to consider recovery models that focus on people, skills and the very nature of work in ways that we haven’t witnessed before — especially in the tourism and hospitality sector.

The 2020 economic crisis has also hit frontline tourism and hospitality workers far more disproportionately than in 2008. Over a matter of weeks, workers have flooded the employment and training networks, compared to 2008 when we saw a more gradual, extended employment decline over the course of a year. The workforce development sector is scrambling to fast-track automated and remote service-delivery solutions. For example, the Ontario Tourism Education Corporation (OTEC) is responding by scaling a tourism and hospitality virtual training and employment platform.

Through these initiatives, and strong collaboration among sector stakeholders, our industry hopes to develop a new roadmap for becoming more resilient and better prepared to respond to future unforeseen challenges.

To that end, OTEC, together with The Future Skills Centre (FSC), recently announced a rapid response project for the hundreds of thousands of tourism and hospitality workers who have lost their jobs due to the pandemic – workers disproportionately represented by young people, women and newcomers to Canada. The program is designed to assist these workers in navigating an uncertain future career path by preparing them to qualify for changing jobs through skills mapping, digitally reskilling and up-skilling.

The COVID-19 pandemic has sped up the digitization of society

Steve Orsini – Distinguished Fellow, Munk School of Global Affairs

One key difference between the 2008 and 2020 global economic crises, excluding the tragic loss of life from COVID-19, is the rapid digital adoption in 2020 that is transforming all facets of life. The COVID-19 pandemic has catapulted the digitization of society more than ever before.

While the digital economy was expanding before the pandemic, virtually everything has gone digital thereafter. Health care, education, the courts, shopping, the arts and social interactions all transformed overnight. As these changes continue to proliferate, society will need to create the supporting policies, institutions, infrastructure and oversight to support a digital economy. At the same time, it will also need to address the digital economy’s potentially adverse effects, where workers become more precarious, global tech giants become more dominant and the digital divide becomes more imbalanced.

Critical to Canada’s success will be an all-of-government approach to fostering an innovative ecosystem – idea creation, commercialization, diffusion and adoption, synergistic spinoffs, reinvesting downstream benefits at home – and providing the necessary support systems – advanced education, leading-edge R&D, universal broadband and 5G, supercomputing powered by AI and big data, data governance and privacy protocols, removal of regulatory barriers and rent-seeking protections, and a competitive taxation and fiscal regime for intellectual property. History shows that creating inclusive institutions promotes entrepreneurship and economic growth that can foster greater innovation and a more socially cohesive society.

Without an innovative ecosystem, Canada’s ability to compete internationally, shrink its growing debt and provide for a more caring and inclusive society will become much more difficult to achieve. Just like the major tax reforms that were needed after the 2008 recession to strengthen Canada’s competitiveness at a critical time, major reforms are urgently needed in the post-COVID-19 world for Canada to become a more innovative, inclusive and interconnected society.

We have rightly spent a lot to provide relief and eventually we’ll need tax reform to pay for it

Alex Himelfarb – Former Clerk of the Privy Council

History provides no perfect analogy for the combined health and socioeconomic catastrophe we now confront. Certainly not since the Depression have we sustained such a broad and deep economic hit. We’ve rightly spent a lot to provide relief and we’re going to have to spend more — depending on our ambitions, possibly a great deal more.

Many of the aid programs will have to be extended, some may have to become permanent, further public investment will be needed to meet the urgent needs of municipalities and get the economy moving. We can expect debates about objectives – whether simply recovery or also repair of cracks tragically exposed, or whether to refashion a more equitable, inclusive and sustainable economy. We can also expect debates about how to pay.

Some economists have urged us to embrace rising public debt; most have advised that we at least get used to it. Now and for the medium term there’s lots of room for deficit spending, especially given Canada’s still-enviable fiscal position: borrowing is pretty much free for the moment and the central bank has been helping by buying government debt.

But debt cannot be allowed to grow indefinitely. Some will argue for a quick return to austerity, though even conservatives warn this would carry enormous human and economic costs. Sooner or later, taxes will have to go up. What that looks like will be contentious, especially amid a recession. Some measures – plugging leaks, closing loopholes, temporary excess-profits tax, higher taxes on the rich – could come quickly, help in recovery and have broad appeal. But if we choose to pursue a more equitable, inclusive and sustainable economy, what will be needed is a reformed tax system that can serve as its foundation.