Last week, the federal government announced an array of new COVID-19 “recovery” programs, newly rebranded from the earlier “emergency response” initiatives. They are intended to get us through the next year. The prime minister is also reported to have big plans for Canada’s social programs to address the “fundamental gaps” in society that have been illuminated by the pandemic.

But it was made clear that all of the new initiatives are temporary. We are still in the calm eye of the storm, and it will not last forever. It is clear that a reformed Employment Insurance (EI) will only be able to meet a fraction of the needs covered by the current array of emergency and recovery benefits that will come to an end in September 2021. For some, the programs that will remain after the pandemic subsides are ill-suited to take on an expanded role, and the consequences, especially for those living in poverty, could be extreme destitution.

Consequently, we need to think longer term and we need to start now, before the “fundamental gaps” show themselves anew and the howling winds begin again.

Will welfare replace the CERB?

Unless a revamped EI program is twinned with a new long-term program to replace the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), many Canadians worry that the end of CERB will mean a massive increase in welfare caseloads and the attendant destitution associated with these programs. They envision long lineups for relief reminiscent of the Great Depression or the large increases that characterized the recession of the early 1990s.

The ’30s and the ’90s experienced massive increases in the number of social assistance (welfare) recipients. The typical rate of 1 in 20 Canadians receiving social assistance moved to 1 in 7 in each of those protracted downturns.

With any luck, the end of CERB will not usher in a renewal of either epoch. It looks like the conditions needed to repeat earlier large run-ups are not in place despite our imminent exposure to the headwinds of a very serious recession.

With promising labour demand, there is little evidence that we will have the prolonged duration of unemployment above 10 per cent that we had in the 1990s. Second, EI will be expanded under the new federal plan, in contrast to the profound cuts that took place in the 1990s. Third, welfare rates for single recipients today are significantly lower than minimum wages compared to the ratios of the 1990s. Fourth, the unprecedented austerity of the 1990s has been replaced by equally novel levels of quantitative easing.

Add to that the fact that social assistance rates have lost a remarkable amount of their value since the mid-1990s. For example, if the current Ontario Works maximum benefit level for single persons without dependents had been increased using the consumer price index, the current monthly allowance would be $1,063 per month – $333 higher than it is now. Clearly there is room to increase welfare incomes substantially.

Could we replace CERB with a universal basic income?

The quick answer is: not now.

Many Canadians are hoping that a universal basic income (UBI) will replace the CERB. Basic income models come in many different forms, along with equally diverse views of how they should be implemented. Regardless of the model, a basic income would take years to implement, so those who support the various models should be sharpening their pencils now for implementation down the road.

I believe a UBI would be big and expensive, in particular for children and seniors – two groups that together account for two-thirds of Canada’s income security spending. The Canada Child Benefit and Old Age Security provide the function of a basic income for these groups. A basic income for all would instead be a solution in search of a problem.

For working-age adults, however, a limited type of basic income may be the answer. We first just have to stop existing programs from fighting with each other.

What can we do with the programs we have now?

Our current income security system for working-age adults age 18-65 spent about $60 billion in 2018-19 before the CERB came along to double that amount.

Most of that spending comes in the form of programs that cover people after they have worked or while they are not working, including:

- Employment Insurance;

- Canada Pension Plan (CPP);

- Social assistance for most recipients;

- Workers’ compensation; and

- Veterans’ benefits.

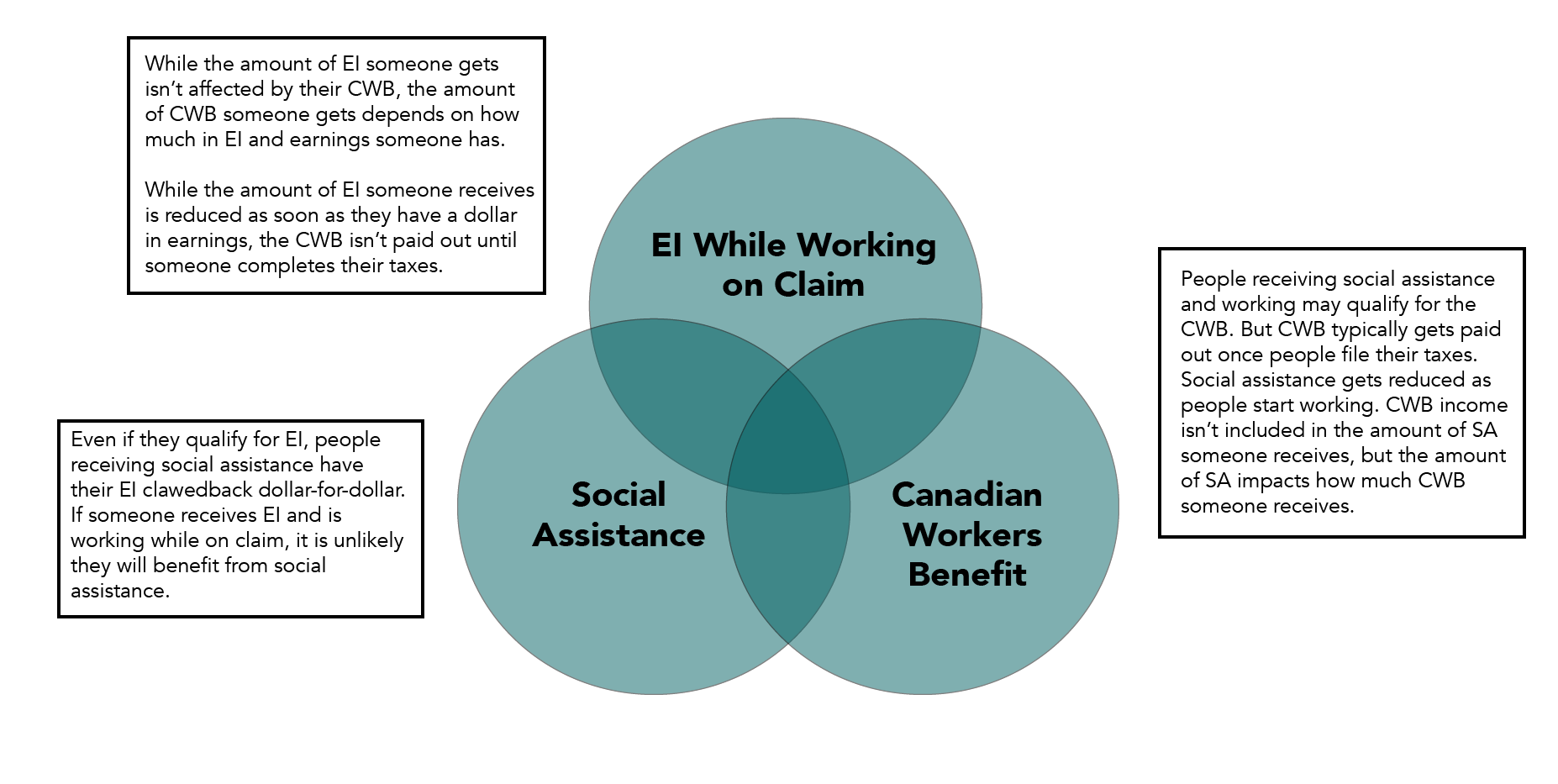

In fact, only three work-oriented income security programs (other than the CERB) allow recipients to work and receive benefits at the same time. These are:

- EI Working While on Claim;

- Social assistance for a minority of recipients; and

- The Canada Workers Benefit (CWB).

These three programs together account for 11 per cent of all expenditures directed to working-age Canadians. They will each gain prominence in a post-CERB, post-COVID world and we need them to work together.

Battling the headwinds: Declare peace between warring programs

As we dismantle the CERB and roll out its three successor recovery programs, we are going to revamp EI for people who do not have work, and many of those receiving the CERB will be transferred back to EI. But in the post-recovery world, that still leaves three other program elements that appear to be at war with each other.

They don’t work together. Each has a different pedigree. EI Working While on Claim is a taxable benefit. Social assistance is not taxed. The CWB is a refundable tax credit.

Together, they resemble the old game of Rock Paper Scissors – they like cancelling out each other. We normally think of welfare as a program that confiscates benefits from other programs. But EI Working on Claim and the CWB have their own “confiscation machines” that are fundamental to their design.

For example:

- Social assistance deducts EI at 100 per cent while exempting the CWB.

- The CWB counts social assistance and EI as income by using these forms of income to lower the benefits it pays.

- EI Working on Claim claws back EI benefits of claimants from the first dollar earned.

- Social assistance deducts benefits usually after very low earnings are achieved.

All three programs could work together rather than cannibalizing each other but no one has ever asked them to. My polite request is that Employment and Social Development Canada, federal finance ministers and provincial/territorial ministers mandate their officials to work together to get these programs to stop pummelling each other.

All three programs could work together rather than cannibalizing each other but no one has ever asked them to. My polite request is that Employment and Social Development Canada, federal finance ministers and provincial/territorial ministers mandate their officials to work together to get these programs to stop pummelling each other.

But even if policy coherence is achieved, these programs together remain insufficient to provide sufficient resources to adults under age 65 who are working. We also need a basic refundable credit – perhaps a much-enhanced GST credit for all low-income, working-age adults.

And we also need the federal portable housing benefit promised in 2017 to kick in as part of the package. After all, it has already begun modestly in both British Columbia and Ontario.

Here are five things we could do in the short- to medium-term once the temporary replacement for the CERB is phased out, to help achieve coherence between the three conflicting programs while closing some of the gaps that remain for low-income Canadians:

- A basic refundable credit for all paid in advance at the federal level;

- A refundable housing benefit for low-income families paid in advance, delivered jointly by Canada along with the provinces and territories;

- A renewed EI Working While on Claim with reduced clawbacks and taxes;

- Reformed provincial and territorial social assistance that allows a broad earnings floor before clawbacks; and

- A Canada Workers Benefit paid in advance (with provincial and territorial adjustments) that phases out based on earnings as opposed to adjusted family net income (which includes social assistance and EI).

With these basic changes, we would be inventing the floor income we need for all low-income working Canadians, and we would not have to fear the spectre of returning to the 1930s or the 1990s.

John Stapleton is an Innovation Fellow with the Metcalf Foundation and Principal of a small consultancy, Open Policy Ontario.