To read “From Stabilization to Stimulus and Beyond: A Roadmap to Social and Economic Recovery,” the full paper on which this article is based, click here.

The COVID-19 crisis is unlike any Canada has faced in the last century. It has forced all but the most essential in-person shared services and supports to cease, and many workplaces have ceased work altogether. The immediate social and economic consequences of the health crisis have left governments around the world and at all levels in Canada improvising to formulate policy responses in real-time. It has also jettisoned many Canadian political, jurisdictional, and constitutional entrenchments about policy delivery.

Canada before the crisis: uneven social policy and cohesion

Canada entered the March 2020 global COVID-19 pandemic with historically low levels of unemployment and comparatively low federal debt-to-GDP ratios, but with escalating external shocks to the price of oil and some emerging concern about slowing growth. Its aggregate buoyant economic profile, however, masked significant existing disparities among provinces/territories, urban and rural communities, and along social axes of inequality (e.g. gender, race/ethnicity, ability and so on). Some of these disparities framed the 2019 fall federal election campaign, with both specific regional economic concerns and affordability in general emerging as central issues.

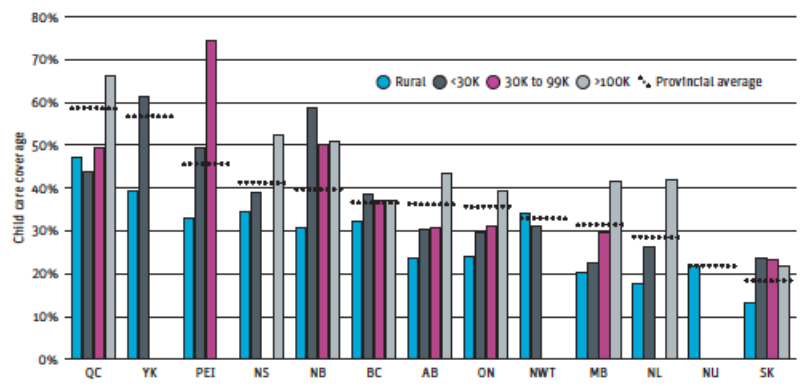

The country also faced the global health crisis with uneven capacity and cohesion: Canada’s complex decentralized structure means that most social policy jurisdiction and social service delivery (including health care, education, labour law, childcare, social assistance) is delivered by provinces and territories. With the notable exceptions of the Canada Child Benefit, health care, and pensions, this kind of federalism results in postal-code social citizenship, in which access, level, and quality of income and social services as well as labour regulation often depends on where you live in the country.

As with many other nations, Canada’s response to the pandemic crisis must also contend with threats by malign actors to its democratic processes, a rise in nationalist and authoritarian populism abroad (to which Canada is not immune) and historically low levels of citizen trust (correlated with income inequality) in information and institutions, including media and government. The addition of the current unprecedented economic and social shock to this backdrop amplifies the challenges for managing immediate communications and compliance measures about health and income policy response mechanisms. Extending beyond the immediate health threat, it also underscores the need to foster a cultural orientation to social solidarity.

Four pieces to inform policy

Social solidarity can serve as a catalyst for economic recovery and as an antidote to social division, including its reactionary political forms. This social solidarity orientation requires deliberate cultivation in planning social policy and in developing stimulus that creates jobs and grows the economy. Care, broadly understood, is at the core of shoring up solidarity. It is central to the immediate imperative of helping Canadians to cope with the crisis, and to establishing essential foundations to our long term social and economic well-being.

The crisis reveals four elements that should inform policy action in the stabilization (short term), stimulus (medium term), and recovery periods (long term).

- Social solidarity

The immediate crisis and policy responses to it call for, and depend upon, exceptional levels of social solidarity. Individual behaviour — including those involving earning, learning, and physical social contact outside of one’s household — is being altered in immediate and major ways. People are adjusting, often at the behest of the authorities, in service of the collective goals of containing the virus, protecting our health system, and ensuring the required foundations for national recovery. Governments at all levels have recognized that achieving and sustaining this orientation to social solidarity is fragile and requires urgent and major public financing. Individuals and businesses require immediate financial transfers to keep money flowing in the economy, to maintain employment ties in order to be able to scale up later and to help them continue to self-identify as workers and members of their organizations. These transfers also help gain support for the physical distancing that remains the best defence against virus spread.

This social solidarity can be quickly fatigued. Its resonance, as well as voluntary compliance with its harsh requirements, relies on a shared sense of duty and purpose, an ability to survive economically and to have hopeful prospects of a return to daily life, and significantly, a sense of fairness in the collective sacrifice. These sacrifices will vary, and many will be life-defining: loved ones dying without families present and without group funerals, businesses ruined and jobs lost, graduations and proms foregone.

- Care at the core

The crisis has enhanced and clarified our collective understandings of what is essential to group life. The often invisible work and tasks that go into maintaining people on a daily and a generational basis — broadly understood as care — are the foundation holding up our shared political, social and economic life. This work is done in households by transforming inputs such as wages or transfers into the necessities of life, and by loving, teaching, and socializing children and others. It always requires investment — and urgently so when work, childcare, and schools are forced to close. This work requires recognition and relies on individual, government, and group funding.

In times of crisis, assuring the work of care becomes even more evident and imperative. Today, it is clear that care work includes essential formal services such as health care work (personal support work, nursing, medicine, cleaning, food preparation, emergency response), community/social work (housing, food banks, mental health, addictions, municipal services and so on), and childcare. In this crisis, food producers, grocery and pharmacy work, and delivery (trucking and postal work) are also folded into the essential care economy. The work also includes a vast range of informal services, including voluntary personal services such as shopping for quarantined friends and family.

The bulk of this essential care work is overwhelmingly feminized, precarious when paid, and among the lowest wage work in the Canadian economy. That this work has now been deemed essential reveals both how our social fabric is vulnerable when recognition of this essential work is weak, and how its labours are an engine that sustains and builds toward recovery. Sustaining and supporting this essential work therefore requires policy pivoting in crisis, in subsequent spending, and in recovery.

- Collaborative federalism and federal leadership

The ideas and policy pathways already in circulation in a crisis tend to be the ones first called upon. The crisis has revealed significant gaps and shortcomings in worker coverage in the Employment Insurance system, and uneven social policy and fiscal capacity at provincial/territorial/municipal/Indigenous levels to respond to COVID-19. This kind of long-standing postal-code social citizenship has demonstrated that where you live in Canada can determine the kind of support available to you in crisis, including the availability and quality of health care, the capacities of childcare, and the generosity of income measures.

Thus far, the crisis has revealed that a national response has been required in the form of policy imagination and innovation to fill the large gaps in our national social insurance system and existing income support policy architectures. Federal leadership has been central to the initial stabilization period to shore up the conditions for care and for social solidarity. The federal government has been called on not just to react, but to be a clearinghouse for a nationally coordinated economic and social policy response. Federal, provincial, municipal and Indigenous collaboration under federal leadership is required now to lay the foundations for economic and social recovery.

- Social infrastructure recovery with childcare as a building block

The road to recovery requires both built and social infrastructure stimulus spending, and a

commitment to sustaining the collective economic and care system against vulnerabilities now visible in frontline essential work. Centrally, this includes investing in building toward a national system of childcare.

In the short term of the current crisis, childcare centres for all but essential workers have been mostly been shuttered. This shuttering, without immediate unique funding streams to meet remaining operating costs, will leave parents, children, and workers with centres unable to reopen when the crisis passes. In the longer term, the path to recovery requires access to regulated and adequately financed childcare.

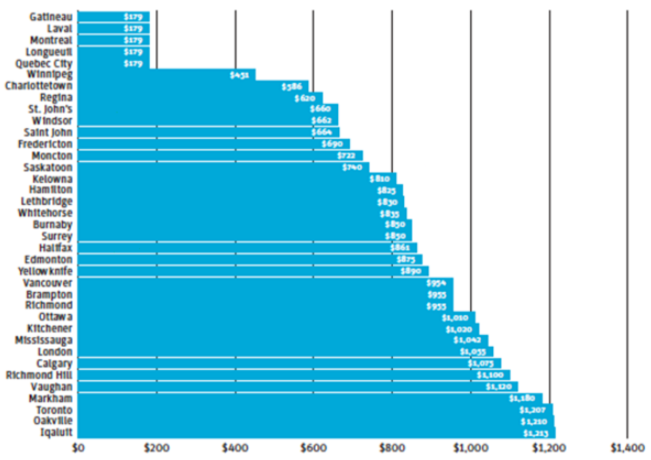

This means different thinking about stimulus spending. The 2008 recession stimulus measures that in the short-term generated employment and growth were disproportionately built infrastructure projects that stimulated male employment — no new federal measures supporting childcare formed part of this recovery. Building childcare systems will necessarily entail investing in built infrastructure (new centres, retrofits, and supply chain inputs) as well as social infrastructure and human capital (early childhood educators, cooks, cleaners, transit workers, snow clearing etc). It will permit the return, and entry of women into the labour market, with the economic heft that such participation and revenue provides. Building care structures will allow people to spend again, ensure that there are consumer goods and other products to spend on, and ensure good jobs are available linked to our main economic advantage, our highly skilled workforce.

In the midst of unprecedented crisis, identifying risks and planning for recovery is essential. Two steps should be immediately taken.

First, stabilize the childcare sector to ensure it can reopen at capacity.

The approach to supporting existing fragile childcare services should be sectoral and systemic. Rather than programs applying for support, the federal government should amend current bilateral agreements to transfer funds to provinces. The amendments would permit provinces to direct immediate, unique funding streams to licensed childcare services that are closed or at reduced operations to meet their costs. This will allow those to fully reopen and reanimate the economy as soon as the crisis lifts. Failure to do so will extend and likely deepen the economic crisis, as care responsibilities will prevent parents from resuming employment.

Second, create and mandate the Childcare Secretariat for Recovery.

The Childcare Secretariat, a promised element of the federal government’s vision for Canada, should be established immediately, with terms of reference amended to reflect the necessities of the current crisis. The Secretariat should be embedded at the centre of stimulus and recovery planning measures, and should serve as a clearinghouse for provincial/territorial system building and benchmark tracking. Building out a childcare system will create jobs in the stimulus period, draw more women into the labour market (with attendant increases in tax revenues), address significant socio-economic inequalities and outcomes for Canadian children, and build a generational fix for deeply entrenched inequalities and social vulnerabilities revealed by the current crisis.

These measures are not a nice-to-have wish list; they are essential to economic recovery. By fostering social solidarity and building social infrastructure with a focus on childcare, we can avoid the mistakes of past recessions, redress the care infrastructure gaps exposed in this crisis, and move from economic stabilization to economic recovery.

Dr. Kate Bezanson is Associate Professor of Sociology, Associate Dean of Social Sciences at Brock University, and specializes in social policy, political economy, federalism and constitutional law. Andrew Bevan is Executive Advisor to Mohamad Fakih, Chair of the Fakih Foundation, and former chief of staff to both a Premier of Ontario and a federal Leader of the Opposition. Monica Lysack is professor of Early Childhood Education at Sheridan College and former special adviser to the Ontario Minister responsible for Early Years and Child Care and the Status of Women.

Dr. Kate Bezanson is Associate Professor of Sociology and Associate Dean of Social Sciences, Brock University, and specializes in social policy, political economy, federalism and constitutional law.