It’s been a rough couple of decades for news organizations. Still, this moment represents perhaps the cruellest kind of dissonance. Canadians are consuming news at record levels as COVID-19 wreaks havoc. And yet, the news across the news industry is uniformly bad. Even though audience numbers are way up, any news organization relying on advertising dollars – which is most of them – has been devastated. With nothing to sell, and facing an uncertain future, that money has all but dried up.

In response, 50 news outlets have closed across the country, and 2,000 people have been laid off, according to one count. Torstar, which owns the Toronto Star, reported that advertising revenue had dropped 58 per cent in the second half of March, and responded by laying off 85 people.

The worst, though, is certainly yet to come. And as the federal government continues to respond to the crisis, any money it spends on journalism should go to news organizations committed to a business model insulated from advertising.

Journalism and advertising had a happy marriage for much of the 20th century. Corporations bought space in newspapers, on radio and on TV to advertise their wares. News organizations used the money to produce journalism while keeping subscriptions cheap, which generated the large audiences that led advertisers to buy even more ads. For a while, it was a match made in heaven.

But that marriage has been on the rocks at least since the internet came along, and the pandemic will almost certainly lead to divorce. Social media lets advertisers reach us in a more targeted way, using the copious amounts of information we share online to make sure their ads are going to the people who are already likely to be interested in their products. Humble Craigslist eviscerated the classified advertising market – why pay to put an ad in your local penny-saver when you can post it online for free? Along with the resistance to paying for news online, which is especially acute in Canada, this has meant a perfect storm for news organizations.

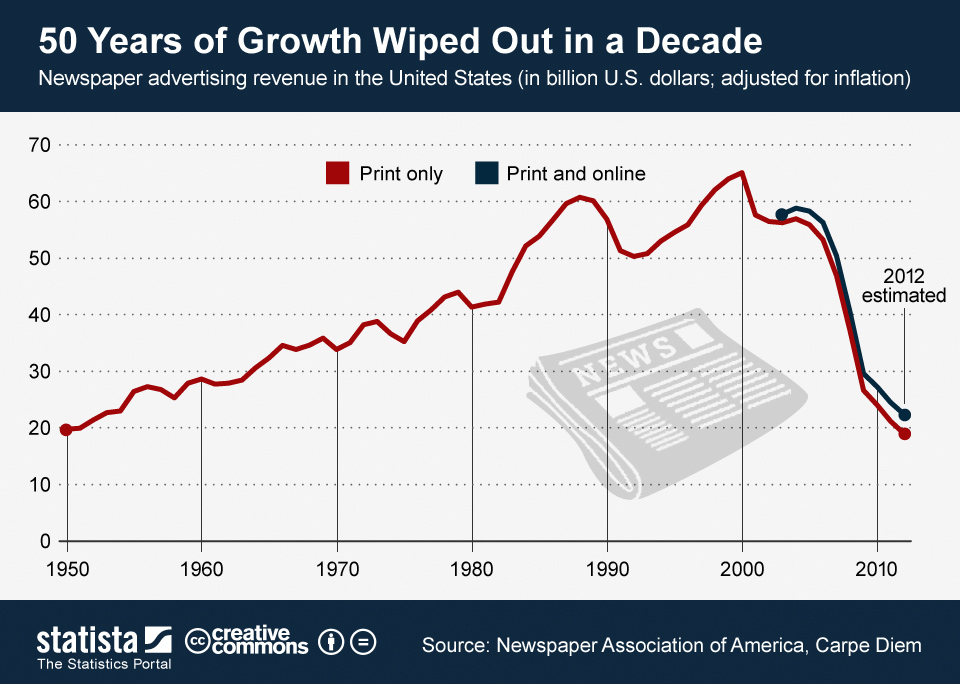

My students gasp when they see the now infamous chart showing newspaper advertising revenue in the U.S.: it rises sharply from 1950 to 2000, and then falls off a cliff, to below 1950 levels in just the next 10 years. In Canada, the chart is less famous but the trend is similar: advertising revenue climbed until 2008, and dropped by more than half in the next 10 years.

This is all old news. And yet, journalism still hasn’t caught up to the changes. And the government is contributing to the problem, with a plan to spend $30 million on ads about the virus in news outlets. This is a quick fix, and might be needed in the very immediate term to tide over these news organizations. Still, it only encourages the unsustainable relationship between news and advertising, which is what led to the problem in the first place.

In the meantime, nonprofit news organizations in the U.S. have been producing journalism with little advertising support for some time. Perhaps you’ve heard of ProPublica or Reveal, funded largely by a mix of big and small donations, or the Texas Tribune, which makes a significant portion of its revenue from an annual festival. Most of these organizations were founded in the last 10 or 20 years as startups that fill a niche in the news landscape: the shortage of investigative reporting in Wisconsin, for instance. But in October, the IRS granted nonprofit status to the Salt Lake Tribune – a first for an existing newspaper. This change may point the way to a future for general-purpose news, those metro dailies that engage in the important but often unglamorous work of, say, covering city hall.

Nonprofit status lets news organizations incentivize donations by offering tax receipts, and compete for foundation grants (many, though not all, of which require nonprofit status). It also helps ensure local ownership, protecting news organizations from acquisition by the newspaper chains known for eviscerating newsrooms.

Of course, it’s not a panacea. News nonprofits still need to bring in revenue. Many continue to sell some amount of advertising. Some host lucrative events. But almost all rely heavily on donations – from individual readers and from foundations or philanthropists.

In Canada, those are harder to come by. The United States has a large number of wealthy foundations, a product of its less equal society. Canadians are less accustomed than Americans to making donations, too. In the U.S., it’s normal for individuals to give to their public library, so it’s not as big a stretch to write a cheque to a news organization.

This means that any plan to start news nonprofits in Canada needs to address how these organizations will be funded. The good news is the government recognized that in 2018. Along with allowing for nonprofit status for journalism, it started a $595 million fund to support struggling news organizations, and created a tax incentive for audience members who buy subscriptions. These solutions are vastly superior to the buy-more-ads option, because they offer revenue that’s not reliant on the rise and fall of the advertising market.

It’s time to make that distinction explicit, in hopes that the news sector will emerge from the pandemic strengthened and better able to do the work our democracy needs. To that end, the government should require any news organization receiving support to work on finding revenue sources outside of advertising. This doesn’t mean all our news organizations need to go nonprofit. Rather, it means that in exchange for government funding, they’ll need to pursue new revenue sources. Maybe the Toronto Star needs to organize a money-making event series for the post-pandemic world, or The Saskatoon StarPhoenix needs a robust membership drive. This on-the-fly retooling of journalism will be tough, but it’s what we need to build a more sustainable industry, and a more sustainable democracy.

We also need to do more to encourage innovation in the Canadian news sector. Down south, Americans are embracing different funding models but also seeing the role of journalism in new ways. In Canada, critics have noted the old media bias of the $50-million Local Journalism Initiative, which will fund 160 reporting positions across the country over its five years, and which has so far overwhelmingly awarded that money to advertising-supported organizations. And the $595 million government fund created controversy for a range of reasons, including the fact that it initially prioritized traditional news organizations, which changed after input from news startups, journalism professors and audiences.

These two funds amount to a lot of money, and we don’t necessarily need more. What we do need is for these same players to work together to encourage a diversity of news startups bringing in a diversity of revenue sources. In the U.S., professional bodies such as the Institute for Nonprofit News gather and teach best practices, encourage collaboration, and help with back-end services. We need our own professional body bringing together and sharing learnings across the news startup sector, both for-profit and nonprofit, with a focus on new business models for news.

We have seen some response to the changing business model in Canada. In 2018, the Desmarais family spun off La Presse, gave it $50 million, and converted it to a nonprofit. That same year the McConnell Foundation made a series of recommendations on the future of philanthropy and journalism in Canada. New digital journalism startups such as The Logic, the National Observer and The Discourse are funded by revenue streams such as subscriptions, crowdfunding or foundations, rather than advertising. The models exist in this country, and now need to be replicated and expanded upon.

One of the most common critiques of the government’s funds for newsrooms has been that it will compromise journalists’ objectivity. Indeed, relying on government funding can make it hard for journalists to report on government. For that reason, the CBC is a Crown corporation operating at arm’s length from the government, and the BBC’s governing charter lays out its editorial independence.

Of course, these protections are not iron clad. Still, foundation funds are perhaps more problematic. Government has a responsibility to be accountable, and mechanisms that work to ensure that. The goals of foundations can be much harder to discern. And unlike advertisers, foundations might not be open about where they’re spending their money, which can lead to convoluted – and secret – relationships with news organizations.

Advertising has the potential to skew news reporting, too, and has been criticized as such ever since it became intertwined with journalism. In other words, we need to be mindful of the potential influence of any revenue source on news. Here again, we would do well to embrace what’s happening in the U.S., pushing for a broad range of news organizations supported through a broad range of revenue sources, to dilute the impact of any single influence.

The good news is Canadians agree that journalism is an essential service that needs government support. As we move in that direction, cautiously, we don’t necessarily need more money; instead, we must make sure that support helps build the sustainable news sector we need, protected from the fickle advertising market.

Magda Konieczna is a Canadian journalism professor living and teaching in Philadelphia, and the author of Journalism Without Profit: Making News When the Market Fails.