This piece is based on survey research conducted by the Environics Institute for Survey Research, in partnership with the Future Skills Centre and the Diversity Institute at Ryerson University. For more details, see the full report: Widening Inequality: Effects of the Pandemic on Jobs and Income.

The COVID-19 pandemic’s devastating effects on Canadians are plain to see. Countless families are struggling to cope with their grief over the loss of loved ones. Hospital staff are exhausted by their non-stop efforts to care for patients in intensive care. Teachers and students are scrambling to salvage what they can from the school year. Business owners and their staff are counting the days until they can get back to work.

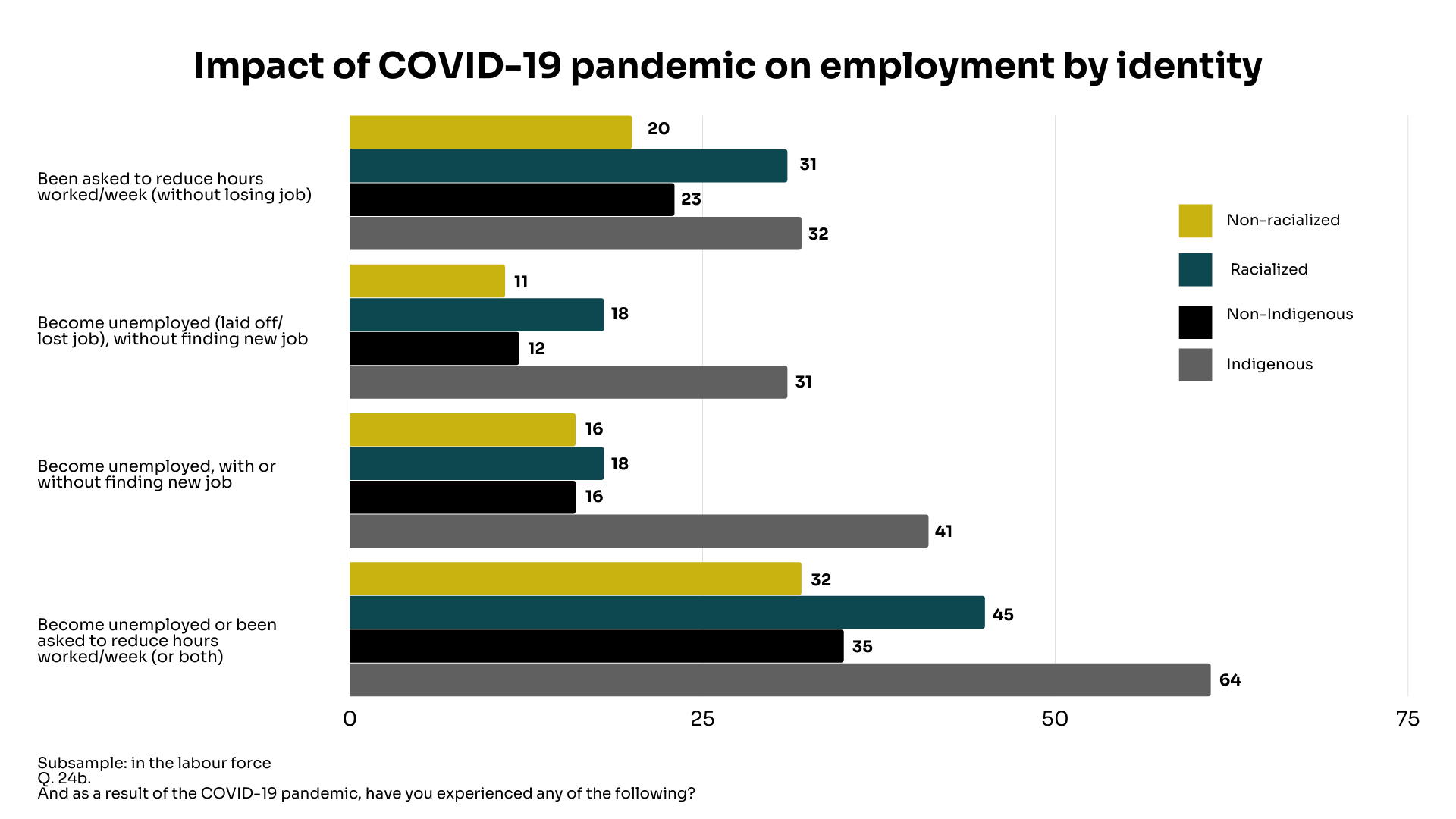

There is one part of COVID-19’s impact, however, that is less visible but no less pernicious: widening inequality. Many Canadians have had to cut back on their hours of work since the pandemic hit, and many others lost their jobs altogether. But underneath the appearance that we are all in this together, the reality has been some types of workers have been affected much more adversely than others. Those hardest hit include younger workers, those earning lower incomes, those less securely employed, recent immigrants, workers who are racialized, Indigenous workers, and workers with disabilities.

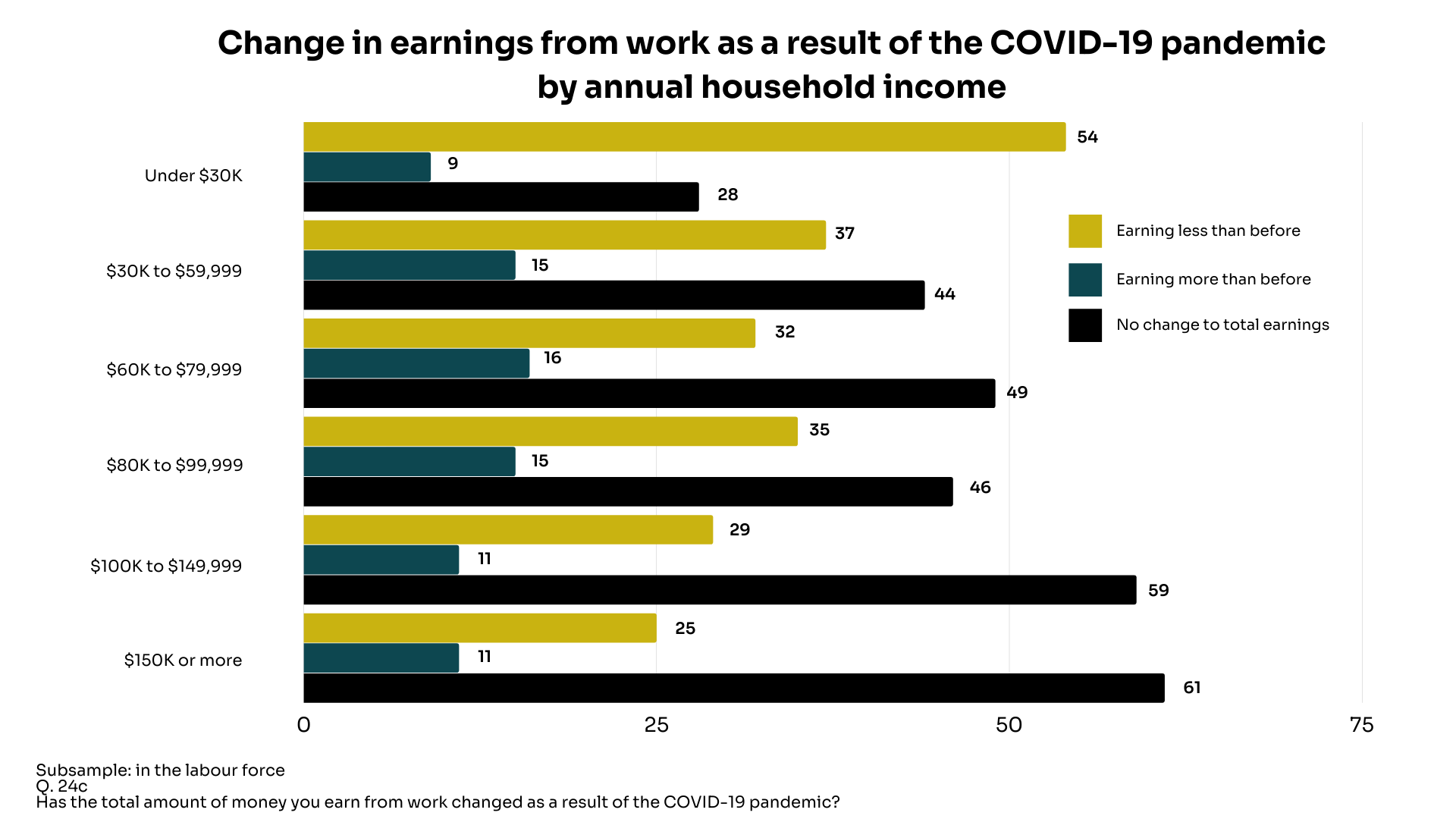

The numbers from our recent survey are stark. Most high-income earners have seen no change to their earnings during the pandemic, while most low-income earners are bringing home even less than they were before.

Those working in sales and service jobs are five times more likely than professionals and executives to have lost their job without finding another one. In the case of Indigenous workers, they are 2 1/2 times more likely than their non-Indigenous counterparts to have become unemployed. Recent immigrants, and immigrants who are racialized, are among those more likely to have seen a drop in earnings due to the pandemic.

The situation for younger workers is especially challenging. Half of the 18- to 24-year-olds in the labour force became unemployed or had their hours of work reduced as a result of the pandemic. Many are now experiencing a prolonged and anxious transition period between the completion of their education or training and the start of the careers.

Certainly, the lifting of restrictions and the re-opening of businesses will help everyone, rich and poor alike. But those hardest hit by the pandemic will not be jumping back in where they left off. They will be starting even further behind than they were before. The gaps between higher and lower earners, between those with more and less work experience, and between those more and less accepted in the workplace will have widened.

However, these growing divides can be easily narrowed again if employers choose to make this part of their recovery strategy. Young graduates entering the workforce with year-long gaps in their resumes can be given a chance. The same is true for newcomers with limited Canadian work experience. Employers can search out employees with mobility restrictions as part of their new openness to having staff work from home.

Deepening the diversity of workplaces and breaking down barriers to inclusion can be put on the front-burner, not relegated to the list of things to get around to only once things are “back to normal.” Recovery and reconciliation can be twinned.

None of these steps should be seen as charitable; they can be self-interested measures to strengthen performance. Employers who make it a priority to combine their re-opening with more inclusive and innovative hiring practices will tap into deeper and more diverse talent pools that will drive their businesses forward. Never has the stage been better set for a win-win scenario. The alternative — a tunnel-vision recovery which leaves until later the challenge of reversing widening inequality — can only mean missed opportunities for everyone.

As the rate of vaccination increases and the number of COVID-19 cases finally falls, we can start to think about an economic recovery. But any economic recovery worthy of its name should begin with making sure these Canadians who have been hardest hit by the pandemic-induced recession don’t fall even further behind.