The global COVID-19 pandemic is reshaping societies and economies the world over as public health authorities take major steps to curb its spread and reduce the death toll. The resulting choices by governments, businesses and citizens have created a social environment that has no precedent in Canadian history. While necessary to combat COVID-19, physical distancing policies create a new challenge for those able to comply with them: widespread disconnection from family and social networks.

By itself, connecting through the Internet doesn’t solve problems of social isolation. But without Internet access, social isolation is likely to get worse — and it’s vital to access services and to participate in this newly compromised economy.

The social isolation scourge

Social isolation is the almost complete loss of contact between an individual and society at large, caused by a wide range of factors including physical health, cognitive issues and gender, among others. The negative health implications of being socially isolated are stark: a recent report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine linked social isolation to a 50 percent increased risk of dementia, a 29 percent increased risk of heart disease and a 32 percent increased risk of stroke. While physical distancing persists, maintaining social connection can help us cope with stress, and remain resilient. While it remains too early to report large-scale trends, we’ve heard from community organizations that social isolation has increased significantly as a result of the current COVID-19 Pandemic.

The people who most need to self-isolate, and who previously experienced isolation independent of the pandemic, may be at greatest risk. An article in The Lancet recently argued that health ministries must take urgent action “to mitigate the mental and physical health consequences” of isolation for elderly people. The Alzheimer Society in Canada has stressed the need to utilize technology to combat social isolation during this period of social distancing. Many traditional services like food drop-offs (meals on wheels) are committed to continuity of service, but have had to modify practices, for example, no longer staying to chat with clients. This further highlights the need to counter isolation in new ways.

Connection is not equally distributed

But how to do this? Four things are essential to facilitating online connection and communication for any individual: 1) a functioning device, 2) a functioning connection, 3) digital literacy to use these assets, and 4) being part of a community in which other people connect online — that is, peers to interact with. There are different challenges associated with supporting connectivity depending on the presence or absence of each of these four factors. And as in so many facets of life, the COVID-19 Pandemic is exacerbating the existing inequalities.

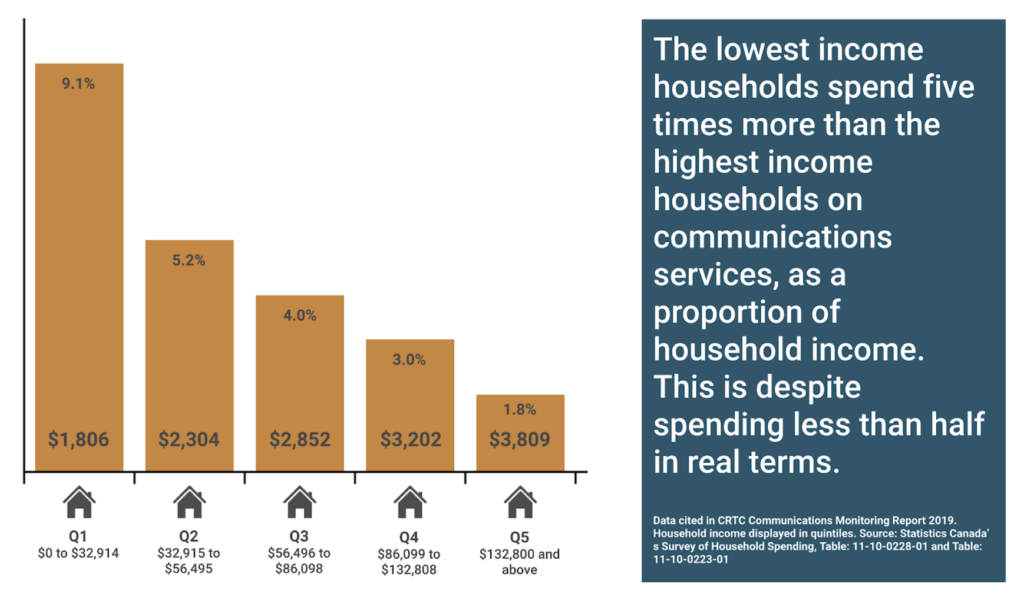

According to CRTC data, in 2017, 69% of lower income households in Canada had Internet access at home. This compares to 98.5% of higher income households. In Canada, 83% of people with a mobile phone have a mobile data plan, but 51% have less than 2 GB and 26% less than 1 GB of data. These are insufficient levels of data to maintain on-going connectivity, especially if a phone is one’s only source of Internet connection. Roughly 73% of lower income households have a mobile phone. Lower income people are more reliant on public Wi-Fi networks, particularly when data caps on mobile plans are reached, as well as on use of computers at public libraries and community centres. Access to both is now highly constrained or impossible. While data caps have been lifted for some home Internet services, none of the four major carriers have made similar changes to their mobile phone data plans. Shaw has taken steps to open up their public Wi-Fi hotspots to use by all – however these are unevenly spread across the country and for most, access would require leaving home.

Indigenous and rural populations already have poorer access, before taking other inequalities into account. For example, CRTC data shows that only 31.3% of First Nations reserves and 40.8% of rural households can potentially access broadband Internet speeds of 50/10 Mbps, compared to 97.7% of urban households. Mobile phone data is available on just 73% of First Nations reserves, compared to 99% of Canadians overall. And where service is available, it is often too expensive.

When it comes to enhancing feelings of social connection online, not all services and platforms are created equal. There is evidence that direct, synchronous communication (e.g. an online video call carried out in real-time), does provide key ingredients for meaningful, fulfilling social contact. On the other hand, more a-synchronous and indirect communication (e.g. viewing and commenting on a Facebook post) can be far less effective, and can decrease one’s sense of social connection. Social connection is best supported online by forms of communication like video calls that require significant speed and data loads. People who are most in need of this form of connection are less likely to have access to it.

What’s being done

Targeted actions are underway to increase home Internet access based on specific needs; for example, for families with children in order to participate in e-learning and this builds upon existing initiatives like the Toronto Public Library’s Wi-Fi hot spot lending program. But the possibility that we will have intermittent social distancing for more than a year places new momentum behind the drive for a universal approach to access – meaning every citizen has the ability to access high-quality Internet. Universal access is needed both to help those people at risk of further social isolation, and also — given the new reality — to facilitate broader economic and educational participation. This will mean addressing access to devices and connections, but also addressing challenges to digital literacy and community uptake.

What can be done

There is an opportunity to immediately address the challenge facing individuals who have a functioning mobile-data enabled device, who regularly use that device, and live in a region with mobile data, but who were previously reliant on free Wi-Fi networks. We know anecdotally that people continue to access public Wi-Fi on mobile devices outside of closed organizations and businesses that still have networks activated. Out of concern for people congregating to access free Wi-Fi outside of closed libraries – counter to physical distancing measures – some libraries in New Zealand have turned off their Wi-Fi networks and shifted to programs supporting individual access. In addition to lower income people overall, many individuals experiencing homelessness who have cell phones would also fall into the category of having a device, but no connection. Two immediate actions should be taken:

- Telecommunications companies, building on the positive changes they have already made to fixed-broadband packages, should provide every Canadian with 10GB of additional free data on every mobile device plan (whether or not it presently includes data) per-month. Virgin Media has already done this in the UK, as has AT&T in the U.S. Video calls use approximately 200MB-per-hour (depending on the quality), meaning 10GB would allow for 50 hours of calls (just over an hour-and-a-half per day). Data could of course also be used for other activities.

- Thinking beyond the challenge of social isolation, telecommunications companies should exempt all relevant online public health information and government aid application portals (e.g. CERB) from any data plan usage. This would require a temporary update to the ruling set in 2017 by CRTC, which currently prevents telecommunications providers from exempting certain content from data caps out of justifiable net neutrality concern.

Now is the time to begin moving towards universal connectivity. As a next step, the federal government should work with all major telecommunications companies (including Rogers, Bell and Telus) to substantially expand the size and reach of existing programs they have in place to offer home Internet at low cost to lower income households, and to loosen qualification requirements.

One option is for the federal government’s own Connecting Families initiative to be significantly expanded, increasing income thresholds, possibly with graduated costs, and including households with and without children.

Currently, the program is targeted to the lowest-income families. To qualify, households must receive the maximum Canada Child Benefit, which means having a net income of roughly $31,000 or below. However, we know from CRTC data that 15% of households with before-tax income of $33,000 to $56,500 still lack home Internet access, irrespective of whether they have children. There is also an opportunity to coordinate a citizen-driven program of device donation and repurposing as a rapid response to the current crisis. This could be supported by government device purchasing and distribution through community organizations to the extent that supply chains will allow.

In the midst of this crisis, community-level intervention is required. In Toronto, some community agencies are discussing how they might facilitate safe use of public infrastructure (including libraries) to provide Wi-Fi and Internet access to those most in need. Others are engaged in trying to address stark realities faced by COVID-19 ICU patients and families who are unable to visit in person through video calls. We have spoken with adult education workers who have relayed the need for highly simplified video-conferencing interfaces to facilitate connectivity for some seniors, for example, tablets featuring a small number of large buttons, e.g. “call John”, “call support worker”. Another spoke to us of the challenge of connectivity for individuals facing homelessness and addictions, imagining a future of outdoor, public Internet-connected kiosks (New York City has taken this latter approach, but its public-private kiosk program has raised serious equity, privacy, and surveillance concerns, highlighting the need for a more direct public service model).

The bigger picture — creating universal access

In the longer term, this crisis must be seen as a catalyst for broader changes in how we provide and regulate the provision of fixed and mobile Internet. In 2016, the CRTC declared that high-speed Internet was essential for quality of life and a “basic telecommunications service” that every Canadian citizen should be able to access. Every major political platform in the 2019 federal election included a promise to improve Internet access, whether that is improving access for rural communities, or bringing in new low-cost plans.

We have made the commitment that everyone in Canada should be able to connect — now it’s time to deliver on it.

The current federal budget commits to ensuring that 95% of Canadian homes and businesses can access the Internet with speeds of at least 50/10 Mbps by 2026 and 100% by 2030, no matter where they are located in the country. $5-billion to $6-billion has been budgeted for rural broadband improvement. While this baseline access is essential, the ability to purchase services is not the same as ensuring delivery. Canadian prices remain high and consumer choice remains a challenge. Reform will require us to rethink the role of government and telecommunications companies, perhaps more in line with our approach to delivering energy and other key utilities.

To meet the aim of universal Internet provision, we cannot continue on our current path. This means acknowledging there have been insufficient incentives for telecommunication companies to expand or improve the network, and that governments across Canada need to take a far more active and ambitious role in ensuring coverage and funding rollouts, given the geographical challenges. We also must address pricing and fairness for customers. This means putting caps on cost increases, and regulating for a low-income broadband package that ensures everyone in Canada has truly affordable access. This is a policy currently being explored by communications regulator Ofcom in the UK.

We must work to ensure that low-income households have a viable option for good quality Internet access with a functioning floor of guaranteed service. At the same time, while acknowledging that there will always be holdouts, current programs focused on digital skills must grow and be improved, working with community organizations, and adapting technologies themselves to specific community needs. Prior to the pandemic, we acknowledged as a society that connectivity was essential. But with COVID-19, it is no longer enough to merely acknowledge what is now an inescapable reality.

Expanding access as an immediate response can build positive momentum toward achieving the fundamental right to connectivity that we know is needed for a prosperous and resilient future.

To develop this article we reviewed relevant research and media reporting, conducted a review of COVID-19 response measures on the four major Canadian Telecommunications companies’ websites (who serve over 91% of Canadians), and sent a short questionnaire to a small number of colleagues, clients and friends in health and community-serving roles in Ontario about Internet access challenges facing communities they serve during the COVID-19 Pandemic. We thank them for their valuable input and continued work to provide vital services through this crisis.

Jon Medow is the Principal of Medow Consulting and a Toronto-based policy analyst and researcher focused on skills, human capital, economic opportunity, and social wellbeing. He has held previous policy and research roles with the Ontario Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities, the Ontario Non-Profit Housing Association, the Mowat Centre, and Higher Education Strategy Associates.

Ollie Sheldrick is a Senior Research Associate with Medow Consulting focused on technology and society, urban sociology and the future of work. Prior to his move to Canada, Ollie served as Research Lead for Doteveryone, a UK based think-tank championing responsible technology, and spent two years as Policy & Research Manager for Go ON UK, a charity focused on adult digital literacy.